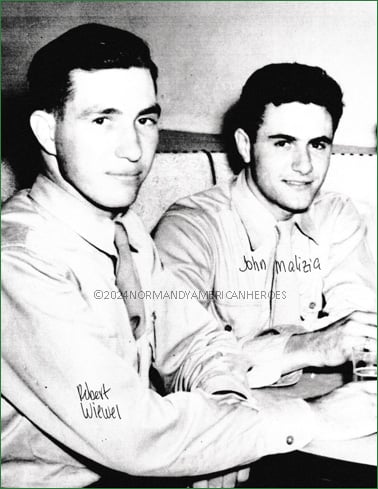

Private Robert Joseph Wiewel was born on September 28th, 1922. Graduated from High School in May 1940, at the age of seventeen years old, he then stopped his studies to help his father, August Wiewel, at the family farm.

Robert Wiewel and John A. Malizia, survivor of the wreck, who claimed that his friend saved his life

Drafted on January 17th, 1943, into the army at the age of twenty years old, he first went to Camp Campbell, Kentucky, and was worried about where he would be sent afterwards, being quite homesick.

Nonetheless, he fought his fears and trained with his company for the pacific.

However, the Battle of the Bulge made the Army’s plans change…

The Battle of the Bulge was Hitler’s last chance to make a breakthough into the Allied lines. It lasted almost one month, from December 16th, 1944, to January 25th, 1945, with the withdrawal of the entire German Army.

It is considered as the last major German offensive on the western front during the Second World War, but also one of the deadliest battle, with 10 733 American soldiers killed and 42 316 injured, and 12 652 German soldiers dead and 38 600 injured.

At the end of 1944, the battle was going strong, and the U.S. Army had lost so many soldiers that they needed reinforcement.

As a consequence, many soldiers left the United States to support those who were already fighting in the Ardennes, instead of joining the Pacific.

A long way from the United States to France...

Robert Wiewel was part of the 782nd Tank Battalion, which left the Camp Cooke, California, on December 14th, 1944. They then stayed in Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, for Christmas and prepared to leave the United States.

They boarded the transports on New Year’s night, leaving the next day from Pier 83, Hudson River, New York.

Robert Wiewel was thus part of the two thousand soldiers who jumped on board of the USS Henry J. Gibbons.

Because of a potential submarine attack, the ship took the southern route, and arrived in Southampton, England, on January 15th, 1945.

On the soldiers’ surprise, they didn’t debark, and directly took the direction of Le Havre on the next evening. From there, they could be sent to the Lucky Strike camp, near Saint-Valery-en-Caux, to get their assignment, be equipped, and join the front.

The Lucky Strike camp.

Among the ten “cigarette camps” in Europe, the Lucky Strike was the biggest. It was used as a staging camp for replacement and named after the famous cigarette brand. The eight others located in France and the one in Belgium, also had cigarette brands nicknames, to avoid potential localisation and attack from the German Army.

The USS Henry J. Gibbons arrived two days later in the north of France, and the men debarked in Le Havre at 0200am on January 17th, and marched two miles to the railroad station.

Finally, thirty-six to forty men of the 782nd Tank Battalion and the 553rd Ambulance Company were boarded into each of the forty-eight cars, counting thirty-six to forty men into each of them.

At that moment, they didn't know that it would probably be their last journey…

Some employees had warned their superiors about the poor resistance of the brakes but were not listened to. The train n°2530 left Le Havre station, first at a very slowly pace, not going up to twelve miles per hour, during the night and on the early morning.

They did a final rest stop about six, seven miles from the destination, in Saint-Vaast-Dieppedalle, before taking the direction of the small town of Saint-Valery-en-Caux.

From this moment, the train began to move faster, for the soldiers and officers’ delight.

But soon, the speed began to be quite anormal, and the convoy, weighting five-hundred and fifty tones was reaching the fifty miles per hour, approaching Saint-Valery-en-Caux’s train station at full speed.

The track was leading around a curve and downhill into the station. As the convoy, rounded the curve, the brakes stopped to function, dragging the train and its passengers to their deaths, as arriving to the station.

Soldiers for most of them didn’t realize the danger of the situation before the crash.

For the driver, it was different since he saw the whole scene without being capable to do anything. Despite his calls of distress, nobody could intervene.

At that point, it was impossible to stop the machine…

Forty yards from the station, on the afternoon of January 17th, 1945, the first cars – the machine, its engine tender, its sleeper-car and eleven wagons - jumped the track, went across several tracks, and smashed into the buffer stop n°2 of the train station.

It then dislocated inside of the building, to finally stop in the basement, as well as on the Train Station Square.

The engine tender had fallen in the basement of the depot and beyond on the track, a dozen cars had telescoped into each other, creating a pile of thirty feet high, imprisoning the soldiers inside. The dozens of cars crashed against each other’s, destroying the first floor, so as the station master’s office.

Behind this entanglement, four wagons hadn’t derailed. Unfortunately, the fifteen following weren’t as lucky, and formed another pile of crushed scrap metal.

According to what the French National Railways district manager wrote in his report, established on January 18th, 1945, the rest of the convoy was well preserved, since it didn’t derail.

So it resulted that thirty-eight cars were wrecked, and only ten were intact.

When they heard the awful noise provoked by the accident, the inhabitants of Saint-Valery rushed to the scene, horrified by what they saw.

They tried to help as they could, before the American soldiers of the neighbouring camps arrived onsite to evacuate the dead and the injured, and to keep the civilians away.

Joseph Falaise (1880-1967), Pastor of Saint-Valery-en-Caux at that time, recited prayers for the dead.

On that day, one-hundred men lost their lives, so as Robert Wiewel… However, no French victim was counted.

The two-hundred and fifty injured were transported into the Saint-Valery’s hospital. The pastor reported that many of them seemed unconscious. In fact, there were especially leg-amputees, due to the fact many of them had left their legs hang outside of the wagons. With the power of the chock, the sliding doors closed violently on them.

They were later transferred to Rouen hospital, which was bigger.

At Saint-Valery-en-Caux, only the French injured stayed. The trainmen, the engineer and the firemen were not seriously injured and were capable to talk. It was thus finally possible for the pastor to understand what happened, asking the engineer what caused the wreck, since many people were talking about a sabotage.

The railroad inspector told Joseph Falaise, the engineer did all he could, trying to stop the train but in vain, and that any blame should be put on him.

After the crash, the 782nd Tank Battalion and the 553rd Ambulance Company reformed and went into action at the crossing of the Rhine, to then fight near Munich.

For the inhabitants of Saint-Valery-en-Caux, it is now a duty to remember the victims

Only five days after the tragic accident, the inhabitants of Saint-Valery assisted to a service at the church, to pay tribute to the people who died on that day.

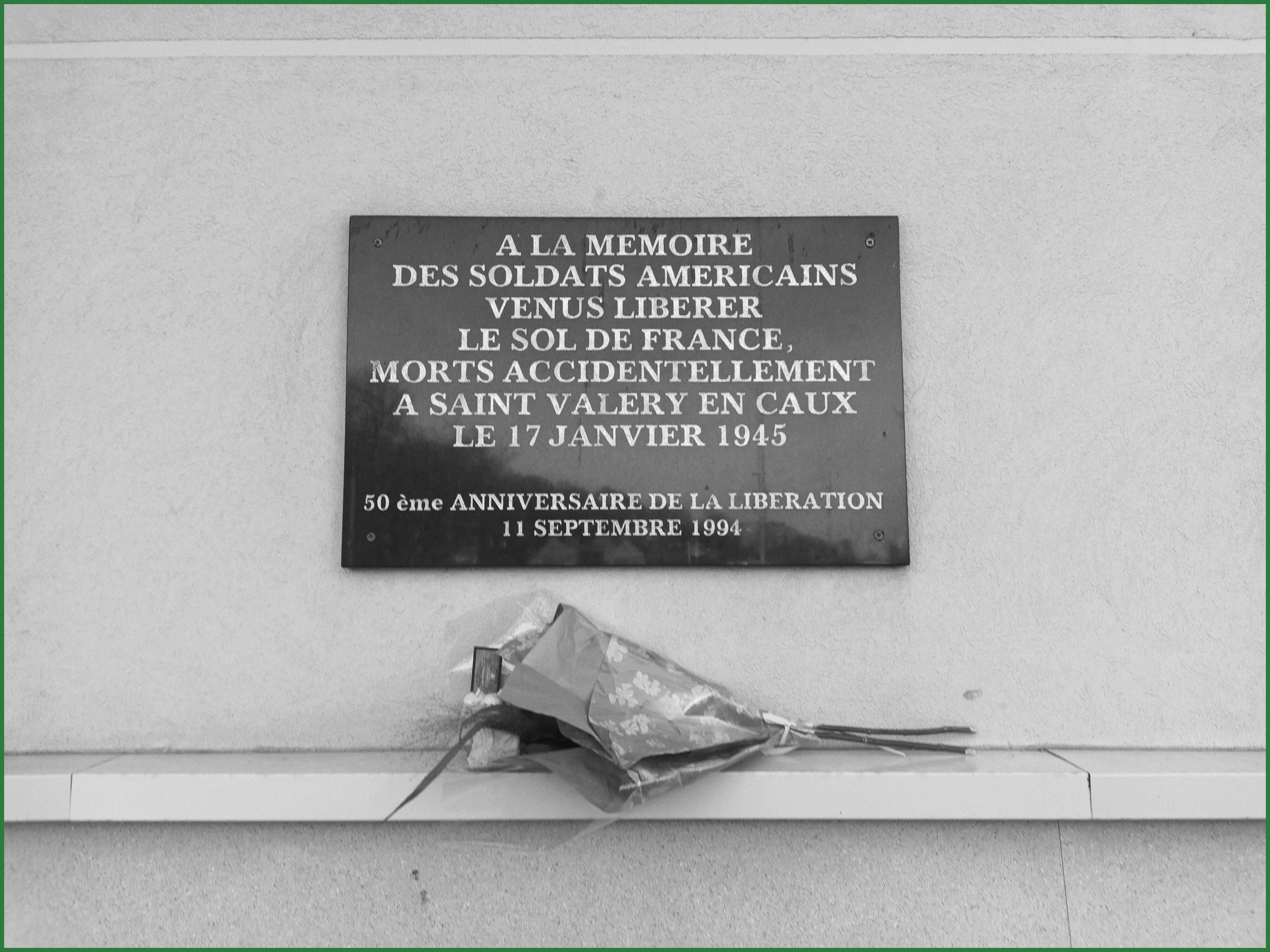

Five decades later, on September 11th, 1994, a memorial plaque was placed against the wall of the actual train station, which was reconstructed in the 1950s, now transformed into an administrative building.

Memorial plaque in memory of the victims of the train accident

The plaque was placed during an official ceremony, presided by the Scottish General Sir Derek Boileau Lang (1913-2001), awarded from the Distinguished Service Order, given by the United Kingdom for operational gallantry for highly successful command and leadership during active operations.

He presided the ceremony in Saint-Valery, remembering the events of 1940.

Indeed, on June 8th, 1940, General Lang withdrew with his division in the Norman village, being adjutant of the 4th Battalion the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of the 152nd Infantry Brigade of the 51st Highland Division after being threatened by the 5th and 7th Panzer Divisions in the Somme, France.

In spite of their heroic resistance, in Saint-Valery-en-Caux, they were forced to surrender on June 12th, after the German army surrounded them. They were imprisoned. General Lang received a medal for his success, after a few tries, in escaping.

At Normandy American Heroes, we were able to come to Saint-Valery-en-Caux, eighty years after the train accident, with our guests, Edward, and Piper Wiewel, in memory of their great uncle, Robert Wiewel, who rest at the American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer.

Ed and Piper Wiewel paying tribute to their great uncle, Robert Wiewel, and to all the men who lost their lives on the crash

They were incredibly received by the deputy mayor, Benjamin Gorgibus, and all his team at the Saint-Valery-en-Caux town hall, committed to perpetuating the memory of the people who liberated the city, and more generally, our country.

Written by Lisa Marie, Trainee at Normandy American Heroes.